I wanted to go back to this blog (after years of not writing anything on it!) to write about something that caught my attention in a Netflix docuseries called Unsolved Mysteries. As of July 5, 2020, it is the #1 most popular show on Netflix in the US. It’s a crime documentary series which details criminal cases that for one reason or another were never closed. But the one that struck me the most was the one in the fifth episode, called “Berkshires UFO.” As the name implies it had to do with what the witnesses and speakers in the episode describe as an encounter, an experience of a supernatural kind. The episode is interesting, first, because it is a contrast to the other cases which featured more human but equally mystifying crimes of violence. And second, because of the structure of the case as it is presented: three families independently give testimony (or so we the audience are led to assume) of a common experience with an extraterrestrial object. In other words, three vantage points of one September night in 1969.

Now I’ve never considered myself a believer (even when I wanted to believe) so I found it fascinating to realize that as I watched the episode, I was, if not growing convinced that they were telling a truth, at least growing empathetic. But how can this be? How can I, a subject of the modern scientific world be suddenly taken up in the language and the thrill of the extraterrestrial? What was it about the testimonies given by these citizens of a small town (small towns being places in which UFOs, our Martian Others, seem to exclusively land) that made me reconsider my usual skepticism, my usual No.

I’ve already said it: language. Or, really, to be more precise, speech: the saying, not the said, which is what the empirical scientist only ever looks at, unaware that the echoes of the truth, as those of a bell, are as much proof of the fact that it has clanged as the clang is its own proof itself. In fact, I’d say the truth of the bell of truth is its echo, its having-clanged. It is the reverberation of the bronze carillon that woke medieval cities from their nightly slumber. The actual clang being only the beginning.

It’s not a secret that I love language. And those that know me best know how central it is to my way of understanding the world. And so it’s not because I want to be obscure that I flip a meaning here or quilt another there but because this is where the frontiers of freedom and symbolic pleasure meet—there is nothing more free nor more pleasurable than white paper and the metaphor.

And so I listen and read. I try to do both of these as consciously as I can, maybe because I know, following Lacan, that language and speech, the baby’s ma-ma, is what opens up the gap between myself and the Other. Even when language is the instrument with which Bertrand Russell tried to teach Scientist Jr. that 1+1=2 (though Gödel said this wasn’t exactly provable), and so is what unites us across education and time and space, language is also what puts at bay. I say the words to you and they open up the gap in which I could be misunderstood. In these words is the gap of the intersubjective.

What I essentially say is that language is as much the source of communion as of excommunication. And again, nothing of what I say is new. It has been said since the 60s. Read up.

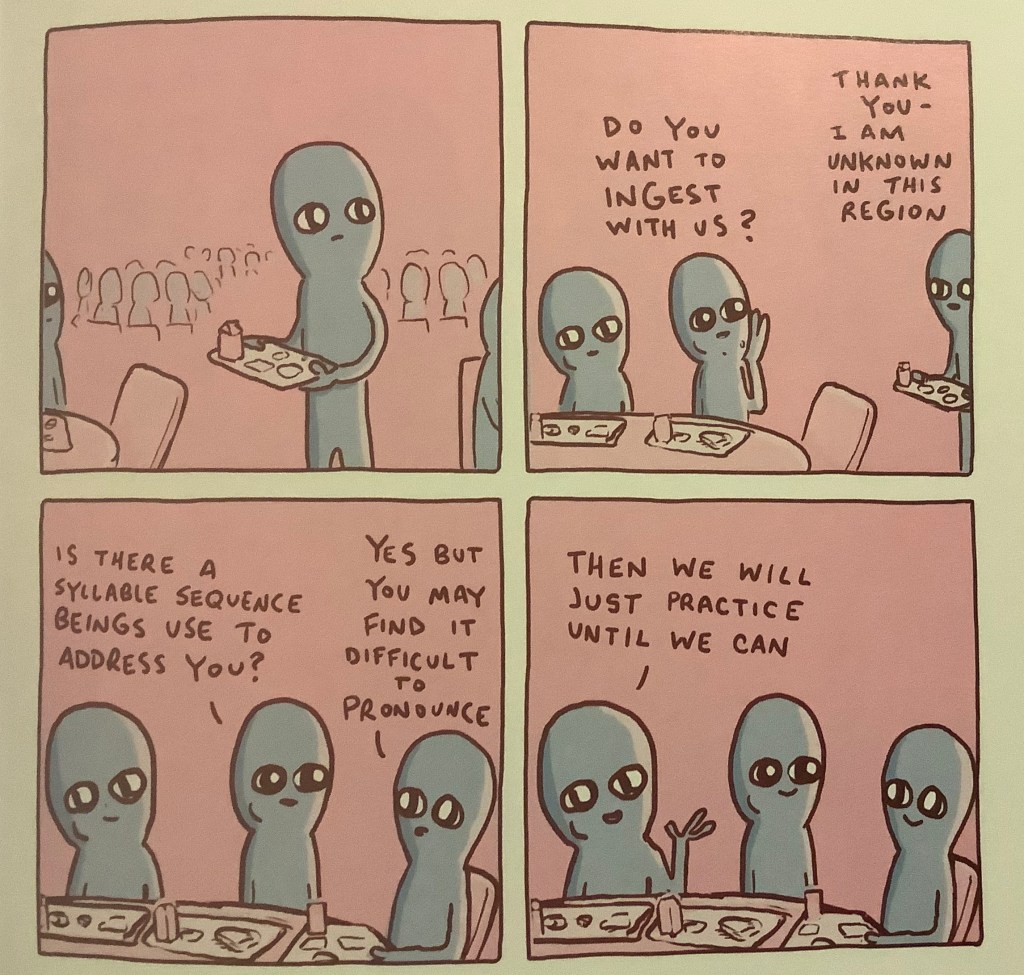

In fact, this same idea is what makes Nathan W Pyle’s comics hilarious. Below is an example.

What is interesting about Pyle’s Strange Planet, is how alienating simple synonymic substitutions applied to your everyday language can be. Here, the alienated being does not “eat” with the others, it (they?) “ingests” with them. It doesn’t have a “name” but a “syllable sequence” (which amuses me). Pyle’s work is all about this uncanniness, this going back to humanity via an altered discourse: if you subtly change how you speak about things it creates this gap which alienates you from the comfort of the everyday, though it is only the everyday that Pyle draws. The Freudian sense of the uncanny is this feeling of disturbance at what returns which was once familiar. A déjà vu, but this phrase is despeakable.

Now the way in which the witnesses speak about the UFO in Unsolved Mysteries is fascinating. The truth is found in speech, as the psychoanalyst well knows. In fact, I’d like to ask if we can use psychoanalysis to glean the truth from their stories, the truth from the lie. After all, no one knows more than the analyst—or the therapist, to be more humane—the lengths we patients go to to keep ourselves hidden even in our speech, especially when this speech is directed at some Other who wants something from us.

I am struck with how believable the first part of each story is, how, as they tell it, they follow almost classical procedures of storytelling. They have their own beginnings, middles, climaxes, denouements, and ends. There is some Thing being said, speaking its truth. And at the same time I am struck by how unbelievable the second halves of those stories are. Unbelievable, not because they got too supernatural, too sci-fi, but rather because they got too mundane. You begin to hear the stereotype. What they begin to talk about is the flying saucer, the probing, the beam of light. In other words, I am no longer hearing the Real of the particular but the Other. What you hear is precisely the language of the out there, the language of the murmurings, of the novels, of the images that have permeated through to the cultural awareness of the issue. The idea that the “alien” probes us is to me actually comedic.

But what I look at is the knot that these two halves in each of the stories form precisely where they meet. The knot is the part of the story that has to do with the direct experience of the “spacecraft” itself.

Maybe, I believe them because their speech is the evidence of something deeply unexplainable, something that is beyond the very possibilities of enunciation. So that, when the poor man is forced to speak about it because he must (no truth wants silence), or because there is a camera crew wanting him to speak for a Netflix special, he must say some Thing: he has to resort to what has been said, what is out there in the novels, in the movies, in the Other (which here just means the collective cultural treasury of symbols). And so for me, I believe him because of his desperate lie, because if anything what he tries to do is pass off a truth as best he can even if it is cheapened by the Already-Said. Indeed, I find it tragic that when he goes to paint his experience on a canvas, he paints something deeply unoriginal: a flying saucer, a beam, and a man. He painted the most general of possible UFO experiences.

Now this differs from religious discourse in that there is nothing larger than the person at stake. So throw out your saintly apparitions. What is at stake is only the person, the trauma.

This of course doesn’t mean that what they say they saw is what they saw. But what I can say is that what they saw is the unspeakable, that from which and against which not even language could cleave its gap.

July 2020

Leave a comment