(Talk given on March 4th, 2020, at Miami-Dade College, West Campus; part of the “Fluid Lines: Philosophy of Gender and Sexuality Symposium” series sponsored by The Humanities Edge)

Before we get into it, and for the sake of clarity, let us define some terms that I will use with some interchangeability but which do have important if not strict definitions: let us define gender identity as what you believe yourself to be: man or woman or genderqueer; gender expression as how this identity expresses itself: masculinity, femininity, androgyny; and sex as the biological characteristics of the body: male, female, intersex, and so on.

Secondly, let me begin by mentioning by way of coyness that though gender is what will structure my talk today it will certainly be about far more than that.

This is not outside the purview of Judith Butler’s field of intellectual interest, for if any of you read her work, you’ll find that questions about gender are rarely raised in her texts alone without some ulterior philosophical question on the self, being, the self of being, and the being of self lurking in the background. As we’ll see shortly, the realization that gender is performed, in her view, can be generalized to include other aspects of our identities, to our sexuality, our class, perhaps even our ethnicity or race. As a result, we can also say that our very subjectivity, that kernel of our consciousness and will, the awareness of which has formed since Socrates the basis for the quest for the good and examined life, may not be as stable as we may imagine, that as Lacan believed, the only thing that holds you together in this world is only a word, a linguistic construction, the word “I,” or perhaps even your name—though, if you’re like me and you’re named after your father, you may not even have that.

Now, certainly, before we delve into the good stuff, before we talk about sex, and penises, vaginas and everything in-between, I am compelled to make two introductory points.

The first is a historical and contextual one and seeks to answer the question, Where does this talk I’m listening to right now fit within the broader field of the gender debate? In no ambiguous terms, Butler argues that gender is socially constructed. Therefore, what this talk will do is hopefully disentangle and clarify whatever that adverb—“socially”—means. This talk won’t debate with theories and viewpoints that claim that social expressions of gender are biologically determined and far less is it going to get embroiled in the on-going scientific debates about the extent to which the molecular and neurochemical differences they’ve found across genders may determine social behaviors. The purpose of my talk is Butler’s philosophical exposition of how a gender can be constructed, how it is revealed as constructed, how an identity can be formed.

The second point I wanted to make perhaps merits no mention or at the very least it shouldn’t be necessary, but I want to make it for the sake of emphasizing the “truth” of one of Jacques Derrida’s phrases: “Everything is discursive.” Why is an English professor, you might ask, talking about philosophy and gender and society? Or what, as Foucault would say, gives him the right to speak? Here I want to bring in Butler who gives the answer: “I originally took my cue,” writes Butler in Gender Trouble, “on how to read the performativity of gender from Jacques Derrida’s reading of Kafka’s ‘Before the Law,’” (xv) which is a text some of you may have encountered in your ENC 1102 classes. My students certainly do. “There the one who waits for the law, sits before the law, attributes a certain force to the law for which one waits. The anticipation of an authoritative disclosure of meaning is the means by which that authority is attributed and installed, the anticipation conjures the object” (xv). I love this. I read the performativity of gender by reading Derrida who read Kafka—this magnificent theory of hers is the product of a literary work filtered three times, or as we say in literary jargon, the theory is a product of metonymic reading, of a process of displacement. In other words, what this example shows is the fertility of the literary work for philosophical interpretation and speculation as well as the importance of reading itself, how reading occurs not just along the lines of the text, but along the curves of the body, and, as in psychoanalysis, through the dreams of the analysand. Again, “Everything is discursive.” Words, bodies, dreams.

The best point of entry into the topic is perhaps the one Butler herself uses in her essay, “Imitation and Gender Insubordination,” which I will use extensively now, and which came after a lecture that she gave at Yale in 1989. She begins with a series of disclosures, all of them tremendously provocative: “I’m permanently troubled by identity categories,” she writes. “I consider them to be invariable stumbling blocks, and understand them, even promote them, as sites of necessary trouble.” Similarly, she writes, “I would like to have it permanently unclear what precisely that sign [meaning that word I] signifies.” Indeed, no words could best characterize the ambiguity of her position than permanent unclarity; ambiguous not because she wasn’t sure of what she was saying but because she recognized the slippery nature of what she was discussing, how the issues of gender and sexuality are excessive, how they shiver with a destabilizing authenticity, how they overflow the psychoanalytic, existentialist, and materialist frameworks. Again, let us use the Lacanian term. There is something REAL about identity. Real because inaccessible.

So, where does this ambiguity come from? “When I spoke at the conference on homosexuality in 1989,” she says, “I found myself telling my friends beforehand that I was off to Yale to be a lesbian [. . .] Since I was sixteen, being a lesbian is what I’ve been. So what’s the anxiety, the discomfort? Well, it has something to do with that re-doubling, the way I can say, I’m going to Yale to be a lesbian; a lesbian is what I’ve been being for so long. How is it that I can both ‘be’ one, and yet endeavor to be one at the same time.” Alright. Let us unpack that.

It is the re-doubling, as she says, that is the cause of anxiety, of uncanniness. Freud called this Das Unheimlich. The disturbance of Dostoevsky’s Golyadkin in “The Double.” It is an anxiety which arises precisely because she is called upon to “be” something once again, to perform what she is—by an institution no less—to go up to a room full of people to be the lesbian who speaks. It is the anxiety of realizing via the performative injunction that, like Derrida’s mime, there is no prior being before the performance, that one’s own ontological status, your being, is the radiated effect of a sequence of actions taken over a lifetime—perhaps in the same sense in which I can only call myself a man, a professor, a son, only by performing like a virtuoso whatever it is that those categories demand for me to be seen as such. As she implies in the Kafka anecdote, the phantasm of a gender identity is anticipated; it is the anticipation that creates this gender identity, the way authority is created by the anticipating man before the law, and it is the anxiety of having to perform the identity to maintain the imaginary reality of that phantasm—a performance that reveals the phantasm—this is the anxiety, the performance that re-doubles, that shows us the irreality of identity.

Now, if you’re thinking that this is all too radical, that even if identity is performed—and notice how I haven’t talked yet about sexual identity though this is the example on which she relies (after all she’s been asked to speak as a lesbian, not just as a woman)—if you say that even if identity is performed say, it is still nevertheless real to you, Butler also has a response for you. “This is not a performance,” she says, “from which I can take radical distance, for this is deep-seated play, psychically entrenched play, and this ‘I’ does not play its lesbianism as a role. Rather it is through the repeated play of this sexuality that the ‘I’ is insistently reconstructed as a lesbian ‘I.’” In other words, my identity is lived, it is important to me, I like to be a woman or a man and do that which I think women and men like to do. I like my big boy truck and I like my pink girly nails. It is not something I can take off of myself without radical sacrifice. I do not act it out as an actor, one who separates his ontological self, his sense of being from that of the characters he or she portrays. The ontological reality of the category may be phantasmatic but not the sense of nostos, of the stability of home that the performance of the category entails for me. Especially when, for example, these performances become entrenched in a wider set of social relations. Or, to keep my example, when I realize that people seem to like me more for my big boy truck or my pink girly nails. Here let me frown at the Hollywood industry.

Now, let me give you another example. The following is a poem I teach by Carole Satyamurti.

It reads as follows.

I Shall Paint My Nails Red

Because a bit of colour is a public service.

Because I am proud of my hands.

Because it will remind me I’m a woman.

Because I will look like a survivor.

Because I can admire them in traffic jams.

Because my daughter will say ugh.

Because my lover will be surprised.

Because it is quicker than dyeing my hair.

Because it is a ten-minute moratorium.

Because it is reversible.

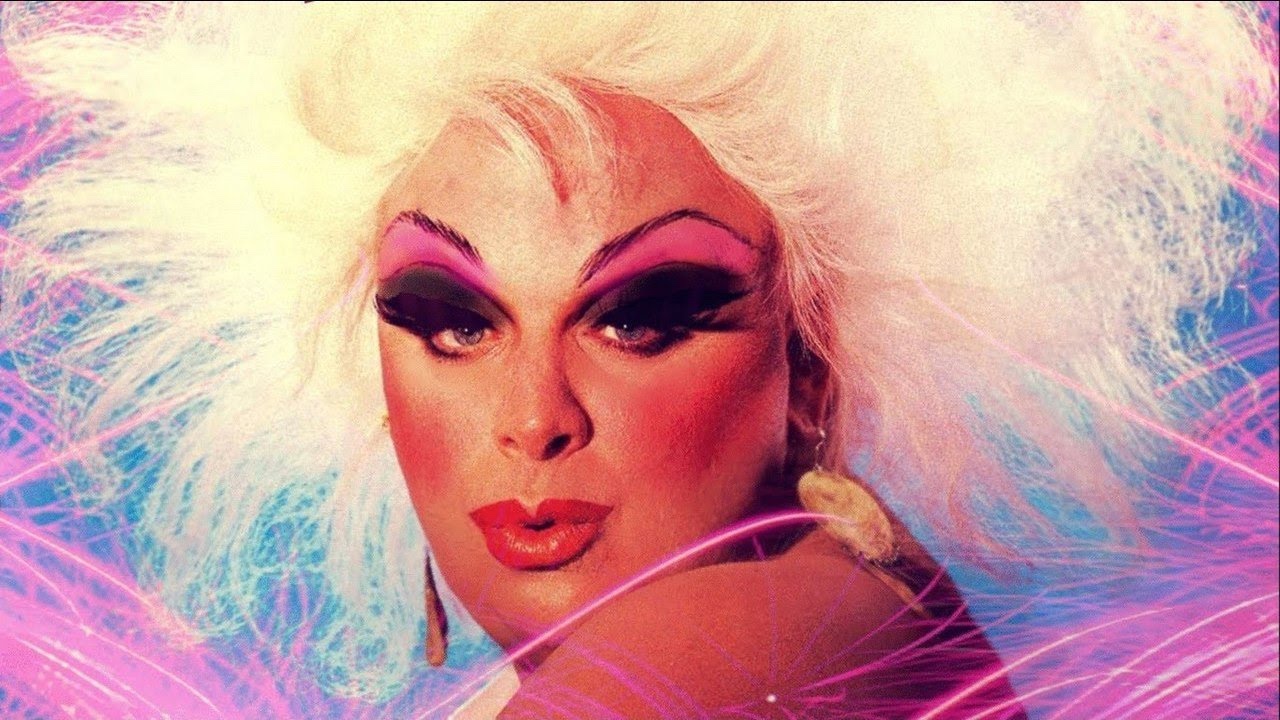

This, I think, is a true gem of the ENC 1102 book. Let us look at the third line. I shall paint my nails red, “Because it will remind me I’m a woman.” Not because I am, but because it reminds me I’m a woman. As if I’d forgotten. As if such a thing could be forgotten. In that line, Satyamurti points out to us the easiness with which this Womanhood is elusive, even forgettable; how it is the ritual of nail-painting that brings back to her the idea of her gender, an ontology—I’m a woman—from an action—painting my nails reminds me of it. Butler will argue that this type of ritual is itself like drag, an impersonation, only that what one impersonates is one’s gender ideal. She argues that in watching drag, she discovered that “drag enacts the very structure of impersonation by which any gender is assumed [. . .] Drag constitutes the mundane way in which gender is appropriated, theatricalized, worn and done.” Notice how the speaker’s daughter in Satyamurti’s poem says “ugh,” as if she were a spectator, though unfortunately not a very approving one. “Gender,” Butler continues, “is the kind of imitation for which there is no original” (1713, GI). And as she says in Gender Trouble, drag constitutes the beginning of the problematic because it reveals itself as the performance of gender: “The performance of drag plays upon the distinction between the anatomy of the performer and the gender that is being performed” (187). The man performs a woman, but the woman, the “she” he becomes, is hyperbolic, a woman re-doubling the make-up, the glitter, the sashay, the kittied-walk. The hair is large, the heels larger.

Drag, for Butler, is a double imitation, one which she says reveals “the radical contingency in the relation between sex and gender in the face of cultural configurations of causal unities [meaning that the union of gender and sex is a culturally imposed “cause”] that are regularly assumed to be natural and necessary. And because it is imitation, gender performance carries within itself the possibility of failure. “Precisely because it is bound to fail,” she writes, “and yet endeavors to succeed, the project of heterosexual identity is propelled into an endless repetition of itself.” In Satyamurti’s poem, the failure is the speaker’s forgetting. The failure is when my mother doesn’t wear make-up when she runs a half-marathon, because as she says, “I don’t need to look pretty to run a half-marathon.” And yet it is all the more reason for why she wears extra make-up when she goes out, when there will be gazes, when expressing her femininity is important.

Now let us shift gears a second. Butler argued a few seconds ago that drag revealed the radical contingency, not a simple contingency, but a radical one, between sex and gender. This brings us to a central concern for Butler.

Butler recognizes the need to decouple the idea that gender emanates from “sex”—and by the way, allow me to put that word, “sex,” in quotations to imply, as in Derrida, a certain irony, a mimicry, as a word with a lot of differánce. This “sex” must also be seen as part of the broader family of concepts under the umbrella of sexuality, which is a construct, a term deployed by a society and its ruling practices to refer not just to the anatomical organ which may or may not be between your legs or to the seemingly irreducible biological facticity or reproduction, but to the range of significations that determine what is sexual, what counts as sexy, what parts of the body are counted as the sites of pleasure—why for example a behind is sexy but not an elbow (for most people). As Butler questions, “If a sexuality is to be disclosed, what will be taken as the true determinant of its meaning: the phantasy structure [meaning what we like to think about, what we desire, phantasize], the act [indeed how many sexual acts are there that don’t involve the sexual organs], the orifice [this doesn’t need clarification], the gender, the anatomy.” All of it is “sex,” sexuality, all of which is a move away from the need of simple animal, or what Slavoj Žižek would call “instrumental,” reproduction. It is this that can therefore be seen, in the Lacanian sense, as constituting that aspect of desire so determinative of the human psyche.

Here allow me to point you to a recent TIME magazine article which has written that “At one Texas college, students came up with 237 distinct reasons that they or their friends had had sex.” 237 reasons! We Lacanian thinkers are always talking about the excess, the lack, the objet petit a, the logic of the not-all, of large systems and the little bits that always endanger them. But 237 reasons! My goodness.

Anyways, certainly, this aspect of “sex” and “sexuality” as being larger than the act of copulation is reflected in the structures of our own language. We say “I had sex last night.” Had? We possessed it and now no longer? Do we not posses sex, our sex, when we’re outside of the sexual act? Why is it that we say we possess it only when the act is occurring? And what exactly do we refer to possess? Why is it that we say we possess it only when the act is occurring? Are we not, as the gender binarists always say, doomed to our sex? Or as Freud remarked, destined by our anatomy? Indeed, this very linguistic construction emphasizes the idea that with regards to sex it is the act, the agency which bestows ontological reality, much like what we just said about gender. In other words, sex becomes real to us precisely in the act, not outside it, and as such our “sex” is something performed, something that is not always entirely successful, that is as plagued by the same issues of failure as gender is, and which, when not successful, is deeply damaging to man’s sense of self, as many men will testify to when they don’t perform.

Now, tied to this notion of the establishment of having (a) sex, via the act of having sex, and perhaps implied by it, is the institutional pressure which forces us precisely into this configuration for the sake of our fulfillment. What I mean by this is precisely the initial point that I tried to make. (Again think how many of those 237 reasons were influenced by institutions? How many of those reasons, for example, had to do with relieving the stress caused by an exam? Because one of the partners saw something enticing in a film?) Society teaches us—in all its self-contradictory ways that sex is not just an act of reproduction, but something, as Žižek says, which must be enjoyed. Certainly a strange, new social imperative. You must do well at it. And you must enjoy it. Is this not what Sex and the City teaches us? It is something that has technique, which entails fulfillment and that is thus constructed.

Sexuality thus becomes a phantasmatic concept, an umbrella term that holds within its shadow anatomical definitions, the act, the field of desire, but most importantly it is the stage where the links between sexuality and power are materialized, rendered audible, displayed. In Trojan Condoms, for example, we find the fascinating union of capital, population control (what Foucault called the Malthusian couple), and the order that says, Enjoy! It is what allows Foucault to talk of the deployment of sexuality, and how governments and institutions use this deployment for the sake of control.

Butler criticizes the many theorists, many of them fellow feminists engaged in their own earnest theoretical struggles, like Monique Wittig and Julia Kristeva, who rely on the assumption that gender emanates from sexuality or that sexuality is, as it were, something beyond language, not constructed, something prediscursive, which later manifests as a gender identity, and that it is this and only this latter manifestation that is oppressed by the patriarchy. Butler dispels the notion entirely, not just for the aforementioned reason—that sex is not a stable, solid category—but also because she avows that our conceptions of sex are already themselves gendered: the penis, says the heteronormative order, must be masculine and not feminine. The feminine penis or a masculine vagina seem paradoxical if not nonsensical. But it is because these two options seem paradoxical to us that the idea of a prior pre-discursive “sex,” which then divides into a masculine or feminine gender is false: for we realize that gender is not an emanation of sex, it does not radiate out, but is already at work when the nurse upon delivering the child and looking at its genitalia decides to say “it is a boy/girl.” If sex was truly prior, then both sexes would have no “gender,” or there would be more than two genders! As Butler writes in Gender Trouble, “If the immutable character of sex is contested [and we have just now done that], perhaps this construct called ‘sex’ is as culturally constructed as gender; indeed, perhaps it was always already gender, with the consequence that the distinction between sex and gender turns out to be no distinction at all. [. . .] gender is also the discursive/cultural means by which ‘sexed nature’ or ‘a natural sex’ is produced and established as ‘prediscursive’” (10).

Now, the impetus with which Butler urges us to decouple gender and sex—a coupling that she says is a normative naturalization of a phantasmatic construction by a heterosexual regime—meaning we begin to talk of a construct as being natural—the way some people say with the dogmatic self-certainty of a priest that there are only two genders because only two sexes are easily visible—and the impetus with which she urges us to see gender itself as drag is owed in no small philosophical part to a curious strain in her writing that emphasizes what we might call an aspect of the imaginary. For where does this gender come from? If gender is an imitation what exactly is the source of the imitation? We’ve talked about the irreality of gender, how it is performance and ritual that upholds it, anticipates it, but there is still a specific performance: in Satyamurti’s poem, there’s a specific action, the speaker is painting her nails red. There is the idea that this is what femininity is for her. The gender that is practiced is precisely one’s idea of the gender, and because of this, gender is contingent upon its historical period. For no subject exists outside of history. As she says, “This formulation moves the conception of gender off the ground of a substantial model of identity to one that requires a conception of gender as a constituted social temporality” (191). In other words, gender is an issue of time—a fact which is absurdly obvious seeing as how George Washington wasn’t called a woman because he wore a periwig and powdered his face. Certainly he must have seen himself a man and done what men did. But if it is performance that determines our gender, then the fact that men aren’t wearing periwigs today while still finding other ways to express their masculinity suggests once again the constructedness of gender. Our conceptions of gender are functions of time. As she continues, “The gendered self will then be shown to be structured by repeated acts that seek to approximate the ideal of a substantial ground of identity” (192). The importance of this ideal is vast for her contemporary work and for her activism.

Central to her critiques not just of patriarchy as such but even of those 1970s feminisms whose discourses had begun to absorb the patriarchy’s masculinist and totalizing universality, is her wish to open up the ground of the possible and the thinkable. What she fears most especially when institutions like lauded ivy league universities ask her to speak as such and such, as a lesbian, as a woman, is the exclusion inherent in the act of being an identity. This is why she promotes them, as she says, as sites of trouble. Always, she asks, in declaring myself as such, am I excluding someone or something of myself. And this disturbance that she feels is not without its foundation, for the project of gay and lesbian liberation is dear to her heart and is constitutive of her thought. She writes, “I sought to understand some of the terror and anxiety that some people suffer in ‘becoming gay,’ the fear of losing one’s place in gender or of not knowing who one will be if one sleeps with someone of the ostensibly ‘same’ gender. This constitutes a certain crisis of ontology experienced at the level of both sexuality and language” (xi-xii). A crisis of being which exists where sexuality and language meet. She therefore effects a synthesis of theory and praxis, as the Marxists would say, a place where one acts and speaks, where one’s ideas and idealizations are contested at the vulnerable point where desire is made manifest. Her project is thus ambitious. It is to denaturalize gender, and she does so “from a desire to live, to make life possible, and to rethink the possible as such” (xxi).

And this happens via language, via presentation and re-presentation. She recognizes that imaginary aspect I mentioned earlier, that ideal phantasm which is in a sense like the Platonic form in which we must participate to be whatever gender we consider ourselves to be, is part of a perceived ontology—in other words, that this issue of gender is deeply tied to our uneasiness of being. Here she points to the need for theory, for philosophical speculation,for complimenting if not moving away from purely biological understandings of gender: I’d argue that we must engage in the old debate of ontology precisely because ontology is wedded to the discussion of gender.

This is evident even in our popular writing and in the crucial topic of transgender identity. In the recent February 2020 special edition of the Time Magazine, which I mentioned some minutes ago and which is dedicated to the science of gender, we have the following quotes: “The physical anatomy you present to the world,” writes Jeffrey Kluger, “may be entirely different from the sense of self you carry inside—something transgender people have long been saying…” (5). Karissa Sanbonmatsu, a structural biologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, who is herself transgender, says, “Even though all of society—parents, school, TV, social media—is telling someone that she’s a boy, somehow, inside her, she knows she’s female.” Lee Ann Connard, who directs the Living with Change Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, says, “Gender is an internal sense, a conviction.” In describing the possibilities of treatment therapies at the hospital, she says that the child can “continue through the puberty of the gender that [they] were assigned at birth or through the gender that [they] are” (21). Sense of self. Insider her. A conviction. An internal sense. The gender that you are. This is the language of being.

I want to conclude this talk—and I hope I haven’t bored you and that despite its density some of the polemic has allowed you to see past the blinds of gender—with a concept on which Butler ends her 1989 paper. It is a fascinating concept to me; it is evidence of Butler’s return to psychoanalysis, to the unconscious as that source of instability of self which neither Foucault not Derrida nor any of the poststructuralists have been able to locate outside the foggy web of language or power/knowledge. “The ‘being’ of the subject is no more self-identical than the ‘being’ of any gender; in fact, coherent gender, achieved through an apparent repetition of the same, produces as its effect the illusion of a prior and volitional subject” (1715). It is via our gender performance that the subject emerges. Rejecting the existentialist position that a subject exists empty prior to predication and signification (so that in this model, for example, gender would be a sort of attached quality to a prior subject, for me to become a woman as de Beauvoir says, I have to have the agency to do so), she argues that subjectivity is the effect of performance. But as she says, “The denial of the priority of the subject, however, is not the denial of the subject; in fact, the refusal to conflate the subject with the psyche marks the psychic as that which exceeds the domain of the conscious subject” (1715). Just as she says that we cannot take radical distance from our performances of identity, even though they are performances, the fact that our subjectivity is an effect of performance doesn’t mean that it is less valid. It just means that it is smaller than the psyche, that our conscious subjectivity, as Freud began to argue in The Interpretation of Dreams and later clarified at the beginning of The Ego and the Id, our consciousness is not the entirety of our psyche, and that, and here I quote Butler, “it is this excess which erupts within the intervals of those repeated gestures and acts that construct the apparent uniformity of heterosexual positionalities, indeed which compels the repetition itself, and which guarantees its perpetual failure” (1715). The repetition of heterosexual identity, she thus argues, must repeat itself precisely because it’s always under threat from the unconscious, because an unthinkable performative move, like the day, for example, a man wears shorts too short, destabilizes the self-assurances of a “natural” gender identity.

And where does this excess come from, Butler asks. What is its source? Sexuality, is her answer. “Sexuality always exceeds any given performance, presentation, or narrative,” she writes, “which is why it is not possible to derive or read off a sexuality from any given gender presentation” (1716). Thus, via psychoanalysis, she provides a second route for the decoupling I mentioned earlier. It is a decoupling that achieves now its full impact: for it allows us to see how a gender identity can be tied by the normative heterosexual regime to a sexual practice. Think, for example, of that archetypal figure in some films, the business executive, a person in authority, who wears a suit five of the seven days of the week, who embodies the regime, who almost wears power on himself, but who you then realize derives intense sexual pleasure by being submissive with his wife, a slave, who cross-dresses, who plays the baby, the naughty student, likes to get spanked, and so on. Butler recognizes that it is the possibility of these sexual expressions that constitute the danger of their transgression. Unthinkable, the heterosexual normative regime says, for a man to look like a woman, because if he loves women, he must look like a man (that does). And yet here he is in garters, in a thong—like that awful episode in Friends where all the boys, out of curiosity end up in thongs, demonstrating the breach, the excess. Again, as Butler writes, “That which is excluded for a given gender presentation to ‘succeed’ may be precisely what is played out sexually.” In other words, we are quite surprisingly kinky behind closed doors. There is thus something authentic about sexuality, something beyond the performative, something perhaps like the Real; it is a disturbance of the Symbolic, a black hole whose dense void reorganizes the topology of our discourses, the grain in the machine.

There is much I would have liked to discuss regarding her thought, particularly this return to psychoanalysis as a discourse whose problematic beginnings do not diminish its capacity to explain these fascinating excesses, these contradictions, these shadows and lacks lurking where the systems of philosophy groan. And indeed, even she herself recognizes as early as the late 80s and early 90s, that there is still work to be done, especially with regards to the provocative issues raised by transgender bodies, their intersections with race and class, and certainly it must not be left unsaid that ongoing reappraisals of our canons of knowledge must continue to stress the importance of inclusivity and representation by undoing the artificial rigidities of categorical thought, of binary systems, of limits, and of all those bars imposed by power and the ways of speaking that serve it. For this is Butler’s hope: that a society that understands the constructedness of those beliefs that it holds to be natural will discover a freer way of being, an open world of possibility, and most definitely, a kinder one. Thank you.

Sources

Beebe, Jeanette. “Fueling Gender.” Time Special Edition: The Science of Gender, 2020, pp 16-21.

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Butler, Judith. “Imitation and Gender Insubordination.” The Critical Tadition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends. Edited by David Richter. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006. Pp. 1707-18.

Kluger, Jeffrey. “The Wide World of Men, Women and Beyond.” Time Special Edition: The Science of Gender, 2020, pp. 4-5.

Leave a comment