My dear, my dearest, how many pebbles is it since I have had the apprentice to sugar you?

Alas, my dear, answers the other, I myself have been extremely unvitreous, my three littlest oil-cakes, etc.

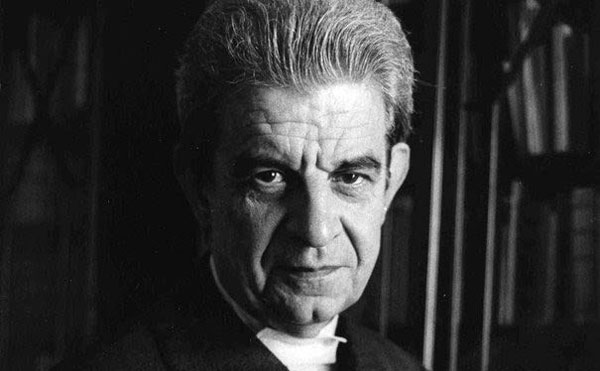

Jacques Lacan, quoting Jean Tardieu, Seminar III, 257-81

In my previous blog post, I talked about one of philosophy’s greatest metaphors, Hegel’s “the being of Spirit is a Bone.” I said, following Žižek, that the metaphor is an openness in the symbolic that allows the subject to come to be. As with anything Hegelian, the concepts are complex. He is saying, not just here but pretty much for his entire philosophical career, that thought is the same as being, and as such, what is real is rational (meaning intelligible) and vice versa. To suspect mysticism is at first not unwarranted. After all, Hegel loved Spinoza and Bruno, both of whom were monadistic thinkers. They liked to think that at the basis of all life is some One to hold it all together. For Hegel, that was perhaps Spirit, the Notion, Absolute Idea. And so, as with any idealism, the problem of the object emerges. How is its reality possible? And if everything is thought, well, how is it that things exist past my conception of them? For this reason, Žižek often interprets the entirety of the Hegelian project as concerned with answering why being appears to itself. In my previous blog, I wrote about this moment, when consciousness supersedes itself to become self-consciousness at the moment it realizes that, along with its self-identity, it is also at the same time a being, a Thing. This self-consciousness is itself the certainty of a statement, what Hegel called the infinite judgment. And this infinite judgment is a metaphor, a Truth: the self is a Thing or the being of Spirit is a Bone. A metaphor thus sits at the very depth of the movement of self-consciousness. It’s an idea I love because it’s almost as if at the very core of what it is to be a human engaging in speculation, there sits a paradox, a deep gash. And we can only get at the truth of this paradox through insight. Hegel warns us that at a literal level—what he calls the level of “picture-thinking”—which sees the subject and object of the infinite judgment in their frozenness, we could only snicker. One has to be a good reader here to understand that he is attacking what would come to be called logical positivism, which postulates the total separation of the object and the self. First, logical positivism will claim that there is a world out there that language can totally represent. Therefore, the world is one thing and words another. Second, there can be and there is a correspondence between words and things. This would make the metaphor a total absurdity, since it would be equating things in language which in reality can never be equal. As a thing myself, I cannot be another thing that is not me. In the metaphor, language would be able to do what the thing it signifies cannot.

Enter Lacan. Referring to the metaphor from Victor Hugo’s Booz endormi, “His sheaf was neither miserly nor spiteful,” he says

[I]t’s clear that the use of language is only susceptible to meaning once it’s possible to say, his sheaf was neither miserly nor spiteful, that is to say, once the meaning has ripped the signifier from its lexical connections.

Seminar III, 248

Like Hegel, Lacan recognizes the superficial oddity of the metaphor. A metaphor works when two things that are not like each other can be identified by virtue of the possibilities of the signifier (of the word). The fact that the metaphor works by identification, by saying A is B, though, of course, A is not B in a literal sense, is why Lacan says that the metaphor is also in the domain of psychoanalytic observation. “The dimension of metaphor must be less difficult for us to enter than for anyone else, provided that we recognize that what we usually call it is identification” (Seminar III, 247). Lacan later emphasizes the oddity when he writes in his Écrits that the “metaphor is situated at the precise point at which meaning is produced in non-meaning” (508). This recalls Hegel, who said that when consciousness utters the infinite judgment while its truth is not accepted, the judgment will simply seem silly. In short, both Lacan and Hegel have a very dialectical understanding of the metaphor. It’s worth noting, too, that Lacan would also attribute a dialectical quality to the relationship between the signifier and the signified so that not only are dialectics found across signifiers but within the signifier-signified relation.

One of the most interesting paradoxes of human behavior is that we have an entire “battering ram” or “treasure trove” of signifiers in our language, an endlessness of words and proliferating avenues of representation that we nevertheless use “incorrectly,” but which, in that incorrect usage, somehow manage to produce meaning. Metaphor is our main example, but it also appears in sarcasm. When a lady responds, “He’s a genius,” while rolling her eyes, she employs a discourse whose meaning is in the exact opposite of what the signifiers are there to signify, and which relies for its effect on the awareness by the addressee of the fact the lady has inverted the signification of her phrase. This does not mean that the signified—the meaning—necessarily exists prior to the signifier (even if something of the intention might). On the contrary, the effect of the lady’s speech, the meaning, is precisely there in the signifiers. There is no sarcasm without the presence of the signifier. She doesn’t just want to say the man is not a genius, that he may be quite stupid; she wants to wound his presence in the symbolic, in the realm of discourse. Lacan realized that in discursive figures like metaphor and sarcasm (or irony), the signifier preys over the signified. “Typically, it’s the signified that we draw attention to in our analysis . . . [But] in misrecognizing that it’s the signifier that in reality is the guiding thread . . . we make ourselves absolutely incapable of understanding what happens in the psychoses.” (Seminar III, 296). And later:

The signifier doesn’t just provide an envelope, a receptacle for meaning. It polarizes it, structures it, and brings it into existence. Without an exact knowledge of the order proper to the signifier and its properties, it’s impossible to understand anything whatsoever.

Seminar III, 296

Notice how this resembles Hegel’s critique of “picture-thinking.”

Lacan extends this discovery to apply not just to psychoanalytic understandings of the psychoses but also to the entire psychoanalytic field. In this case, he was perplexed by how the psychotic subject, who suffers from paranoia, delusions, and visual and verbal hallucinations, was inundated by the signifier in their psychotic episodes. Lacan sees metaphor (and its close relative metonymy) as useful in talking about the psychoses because he subscribes to the idea that the workings of the unconscious function like a language (see Écrits 295). In other words, if the unconscious is the realm wherein our drives, desires, repressions and so on exert their effects precisely as signifiers, and if the relationships between all of these follow, shall we say, a grammar, then it stands to reason that metaphor and metonymy operate there as well. Indeed, he sees himself as following Freud: “what Freud calls condensation [in The Interpretation of Dreams] is what in rhetoric one calls metaphor, what he calls displacement is metonymy” (Seminar III, 251). Lacan thus finds in the workings of the Freudian unconscious these same devices at work.2

Supposing the unconscious is thus structured like a language and that what constitutes it is the signifier, Lacan postulates that psychotic patients at the mercy of all sorts of hallucinations are subjects inundated by the signifiers in their unconscious. It’s as if the psychotic subject was bearing witness to a discourse they are expelling and allowing to introject again. Lacan figured that signifiers that were once relevant or even important to a subject were “depersonalized,” sent out there as if the subject had ejected them. So he asks how it is that a personal speech, a set of symbols, a personal discourse, could still be felt to be impersonal, another’s. Think of a lifelong gardener, for example, who, because of some psychotic break, hallucinates a Venus fly-trap is eating him. The little innocuous plants are no longer what they were for him, and the hallucination forces him to see them in a radical alterity.

Lacan thus tries to apply his ideas on metaphor and metonymy to the issue of the psychoses to see what he can glean of the psychotic’s unconscious. But first, he takes a detour into the aphasias. Aphasia is, according to Google, the “loss of ability to understand or express speech, caused by brain damage.” Lacan mentions how an aphasic is a subject who has access to language, to the synchronic treasure trove of signifiers, but who can’t ultimately say what he wants to say. “He will say— Yes, I understand. Yesterday, when I was up there, already he said, and I wanted, I said to him, that’s not it, the dots, not exactly, not that one. (Seminar III, 249)

Lacan realizes that the aphasic can use metonymy (which he calls contiguity, following Roman Jakobson). He can form the beginnings of sentences, as if he knew how to use language, but he can’t say the very last word that would grant them their meaning. “These unfinished sentences are in general interrupted at the point at which the full word that would give them their meaning is still lacking but is implied.” (Seminar III, 294). Indeed, the jarring effect is produced because the crescendo of meaning in the sentence is cut off at the precise moment before its completion, to the point that Lacan even hints at the possibility that you can guess that last missing word. Lacan believes the case parallels that of the psychotic subject. In both cases, there is the foreclosing of a signifier that was once theirs, that has escaped from their control and left the subject either mumbling (in the case of the aphasic) or at the mercy of hallucinatory episodes (as in the case of the psychotic).3 As Lacan says, “The imbalance in the phenomenon of contiguity that comes to the fore in the hallucinatory phenomenon, and around which the whole delusion is organized, is not unlike this [the aphasia]” (Seminar III, 250).

Now, as regards metaphor, the issue is a little more complex. First, again, we have to start with a provisional definition and say that a metaphor relies on some similarity between signifieds. If I say “the cat is a moon,” well, it could be because the signifiers “moon” and “cat” signify creatures and things that often appear in the dark, when the sun is not present, and so on. The metaphor itself would thus be a signifying phrase that represents that similarity; it would be the signifier as such of the similarity between concepts.

But Lacan’s point is the opposite. The signified doesn’t just determine the meaning and lets the signifier carry it. Rather, the signifier itself fundamentally alters or distorts the meaning and forms part of the metaphorical process.

The naive notion has it that there is a superimposition, like a tracing, of the order of things onto the order of words. It’s thought that a great step forward has been made by saying that the signified only ever reaches its goal via another signified, through referring to another meaning. This is only the first step, and one fails to see that a second is needed. It has to be realized that without structuring by the signifier no transference of sense would be possible.

Seminar III, 255

And later:

The important thing isn’t that the similarity should be sustained by the signified—we make this mistake all the time—it’s that the transference of the signified is possible only by virtue of the structure of language.

Seminar III, 258

Lacan doesn’t say that two signifieds can’t be identified with each other via metaphor because they’re similar. They certainly can. But instead, he says it’s not similarity alone that is the condition for the birth of a metaphor. The condition is simply the positional nature of the signifier in the structure of language. Signifiers like words or even traffic lights have their meanings because of their position, either in the sentence (in a language such as English or French)4 or quite literally in spatial relation to objects. For example, a red light over a door may determine moments of entry and non-entry, but a red light in the void may mean nothing even if it titillates! As a result, anything can be metaphorized; any signifier can be identified with another signifier. Speaking about the metaphor from Victor Hugo’s Booz endormi, Lacan says that what gives Booz’s sheaf its metaphorical quality is “that the metaphor is placed in position of the subject, in Booz’s place” (Seminar III, 252). Lacan points out that it is a characteristic of language that can allow the override of a signifier by another. More interestingly, the overriding signifier can take the place of another signifier that stood for a subject. If the signifier “Booz” was the inscription of a subject in the texture of language, if that was where Booz was, there shall the sheaf be; there shall it be. What breeds the metaphor is simply the structurality of language, the capacity of the signifier to be fluidly exchanged.

Now, what does this all have to do with psychoanalysis? Forasmuch as a psychoanalyst deals with the subject’s unconscious, the psychoanalyst deals with a symbolic order at work in the subject. What does the psychoanalyst do if not interpret the signs and the disturbances in the unconscious by way of the subject’s endless symbolizations of their world? The analyst touches on the subject’s “relation to the signifier—in this case, by changing the procedures of exegesis” and in so doing “changes the course of [the subject’s] history by modifying the moorings of his being” (Écrits, 527). A central point in the Lacanian world is that these “moorings of being” are nothing other than signifiers. It is thanks to our human capacity to symbolize by way of the signifier that we can be who we are. Furthermore, an interesting point that Lacan begins to make is that it is as a signifier that a neurotic symptom manifests. As a simple, evocative example, why is it that, in her famous case, Dora begins to suffer from dyspnoea if not for the fact that (among other related things) she was symbolizing the trauma of Herr K.’s sexual advance in the oral region of her body? Indeed, one of the most emblematic positions of (middle) Lacan5 is the idea that the symptom itself is a signifier of repression. And, if this is the case, does this signifier then not work metaphorically? If the repressed is an unconscious signifier and the symptom is the signifier for which it has been traded, can we not say that the symptom is a metaphor?

[I]f the symptom is a metaphor, it is not a metaphor to say so, any more than it is to say that man’s desire is a metonymy. For the symptom is a metaphor, whether one likes to admit it or not, just as desire is a metonymy, even if man scoffs at the idea.”

Écrits, 528

Lacan thus takes an interestingly defensive tone, as is typical of his enormous ego, but so did Hegel. Both thinkers are aware that something about the metaphor is easy to resist at a superficial level. It is easy to repress it, to avoid it, to not come to terms with it. I’ve heard many people say they don’t like poetry because they can’t understand it and the mere reading of a metaphorical phrase angers them enough to set the whole task aside. It’s almost as if Hegel and Lacan had found a sort of foundation in the metaphor as a figure of language. For Hegel, the metaphor the being of Spirit is a Bone is an enunciation of a consciousness that has the Notion of Reason. For Lacan, the metaphor is a function of the unconscious-structured-like-a-language, making possible nothing less than the symptom itself. Metaphor, the substitution of one signifier for another, is the mechanism by which the subject can produce complex meaning, can link signifying chains together. In short, much like Hegel, it bears the subject as the subject is in the world. So that it would not be unfair to modify Freud’s old dictum and say, Where the metaphor was, there shall I be.

- All quotations are taken from the available English-language Norton edition seminars and Bruce Fink’s translation of the Écrits. Where applicable and available, the page numbers refer to the French Éditions de Seuil, which will also be found in the Norton editions of the third seminar and the Écrits.

- This description of the unconscious is also somewhat incorrect in the Lacanian sense. In Seminar I, Lacan writes that the unconscious “is a self and not a set of unorganized drives, as a part of Freud’s theoretical elaboration might lead one to think when one reads in it that within the psyche only the ego possesses an organization” (66). For Lacan, the unconscious is another structural “I,” one whose (virtual) existence depends on the discourse of the Other, that is composed by the signifiers of the Other, and is not simply a receptacle of a person’s repressions or desires. Here, Lacan sticks closer to early Freud, who likewise saw the unconscious more like an alternate mental function than a “container” of dangerous, inadmissible drives and wishes.

- There is a comment to be made about the similarity between the aphasic’s speech and, let’s say, a modernist text by Samuel Beckett or even one of these new “creative” works by computer algorithms. It’s hard to think that a figure like Lacan or Adorno would not find the aphasic’s speech a fascinating discourse to listen to since they had their own personal fascinations with surrealism (in Lacan’s case) or modernist literature (in Adorno’s).

- What could we make, then, of a language like Latin in which order doesn’t matter?

- This idea would undergo some change—as all ideas should!

Leave a comment