I always hear myself saying, “She’s a beauty!” or “He’s a beauty!” or “What a beauty!” but I never know what I’m talking about.

Andy Warhol

You either know too much about Andy Warhol or too little. You know him either as the whimsical exemplar of Pop art or as the deeply conflicted conceptual artist who turned the portrayal of paradox and contradiction into an art form and a business. Once you decide to learn about it, something of Warhol’s life resists cursory reading, which is also why there’s no “middling” awareness of it. As soon as you dive into his life, you discover a set of profound questions that shatter all preconceptions you may have about art.

As an example, recall that in 1985, Warhol exhibited himself as his own artwork for an art installation at the Area nightclub. He stood there gazing at his onlookers next to a label that said, “ANDY WARHOL, USA, INVISIBLE SCULPTURE, mixed media, 1985.”[1] It was an utterly ingenious piece. It was Pop art, insofar as the subject was “Andy Warhol,” the celebrity; it was conceptual art insofar as it forced the viewer to ponder about the “invisibility” of the work—about the nature of the mask, of symbolic identity, his place in the regime of meaning; and it was performance art, insofar as Warhol himself had to act as himself, as the ever aloof, enfant terrible of the art world, the ever-mercurial nymph of artistic endeavor who would stop at nothing to seek the eye of fame while acting as if the fact of being in front of so many eyes was an unendurable burden. Gopnik puts it magnificently:

Only by presenting himself as Andy Warhol the artwork did Warhol finally get to take off the Andy Suit he’d always worn when he had to play artist. He had become his own Duchampian urinal, worth looking at only because the artist in him had said he was, earning the right to do so thanks to decades of artistic labor.[2]

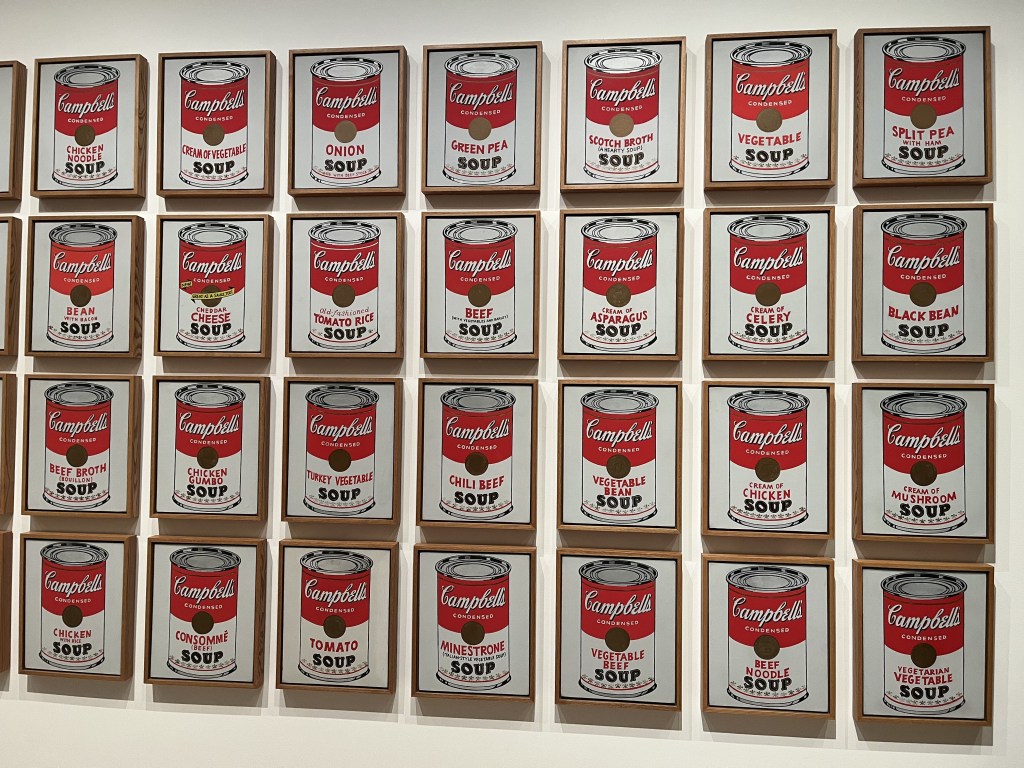

Indeed, elusiveness is a word that aptly describes much of what you can call Warholian and not because Warhol’s works lack clarity, but the opposite: Warhol was too obvious about what he was doing. There is no ambiguity of representation in the stark coolness of his 32 soup cans of 1962, in the Brillo Boxes, nor in the Flowers. In what you could call a maximal commitment to realism,[3] Warhol took objects out of the supermarket and placed them on the canvas as if they were icons.[4] The objects in front of you are thus unveiled. Nothing inhibits an immediate recognition of the Brillo boxes or the Del Monte tins, especially in the 1960s when canned goods were more attractive as goods than they are today. And yet it is because of this seeming openness that the painting recedes. Immediately, the viewer will wonder why a soup can is there in a gallery in the first place. Or why the Brillo boxes, identical to their real models, would count as “art.” Warhol’s penchant for forcing his viewers to engage in the ponderous task of having to sort out their feelings about what they think art means or ought to mean put him in the same category as early conceptualist artists like Marcel Duchamp or Yves Klein, who loved to confound their viewers with their work.

But, unlike Klein or Duchamp, Warhol would use that ambiguity, that space opened up by the radical maneuver of painting something so banal that it could only lead his audiences into philosophical conundrums to stretch the frontiers of art to breaking point and take the art world into regions that it had sought to avoid since the Romantic period: commerce. If, in Warhol’s postmodern era, the definition of art is unclear, if we simply cannot provide the rules and standards by which we could determine whether something does or does not belong in a museum or in an art gallery or even on a canvas, then anything could count as art. We could modify Dostoyevsky’s famous saying—“If God doesn’t exist, then anything is possible”—and write, “If art is undefined, anything can be art.”

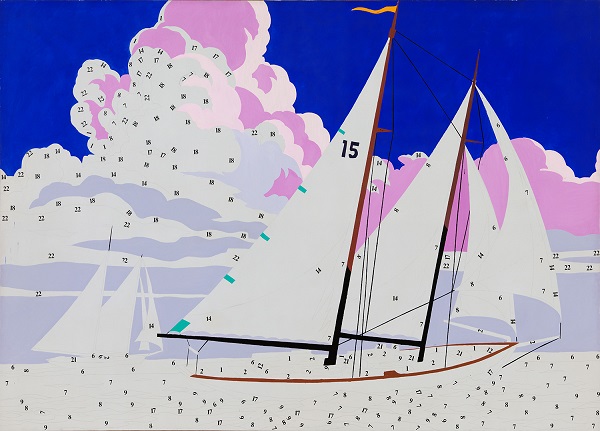

A fascinating example of this attitude, this deep philosophical fissure, is Warhol’s Do It Yourself series of 1962. For this series, Warhol enlarged paint-by-numbers images and filled in some sections so that the effect would be of an incomplete painting that asks the viewer to finish it. Not only does Warhol cede his authority of the work to the viewer, but he also enacts a conceit wherein our participation will produce a set of identical “originals” insofar as we follow the numbers scheme. At the end of the experiment, the only unique painting would be Warhol’s own first model precisely because it’s incomplete. Thus, Warhol creates a situation in which the truly original piece is both incomplete and the one that instigates its own relinquishing of authority.

Warhol and the History of Art

The more I’ve read about art, the more I’ve noticed that it’s almost as if the history of art is the set of questions posed by each era’s artistic production and legitimated as proper questions by the societies in which they’re asked. Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer, an exemplar of Romantic painting, raises the question of the relationship of men to the seeming violence of nature, a propitious question at a time in which the rift between speculative philosophy and science was widening. And the Ancient Greek temple, as Heidegger noted in “The Origin of the Work of Art,” raises the question of the nature of the Divine that needs a dwelling to enter into communion with humankind, a question of immediate resonance for the Greeks who had begun questioning the relation between grand conceptual ideas and ethical human behavior. Regardless of the angle of attack, each work of art elicits intractable quandaries that go to the heart of how a society makes meaning. For this reason, the development of art is in close conversation with historical and political development. In other words, we could say with Lacan that the work of art poses a question that uniquely reverberates in the symbolic. Thus, the work that is so different or so impossible or so lacking in resonance is ignored not because it has nothing to say but because the question it poses is not yet one its recipient society can or is willing to understand. That work thus falls into nothingness. The question it poses simply dissolves or gets archived, as it were. An example of this is, perhaps, David Jones’ Anathemata, a modernist masterpiece every bit the equal of Eliot’s Wasteland but, I’d argue, largely unknown.

The mind-boggling question Warhol posed is a spin on the Duchampian. It is not just a repetition of “What is art?” but more precisely—and catastrophically—“What is art that can be sold?”

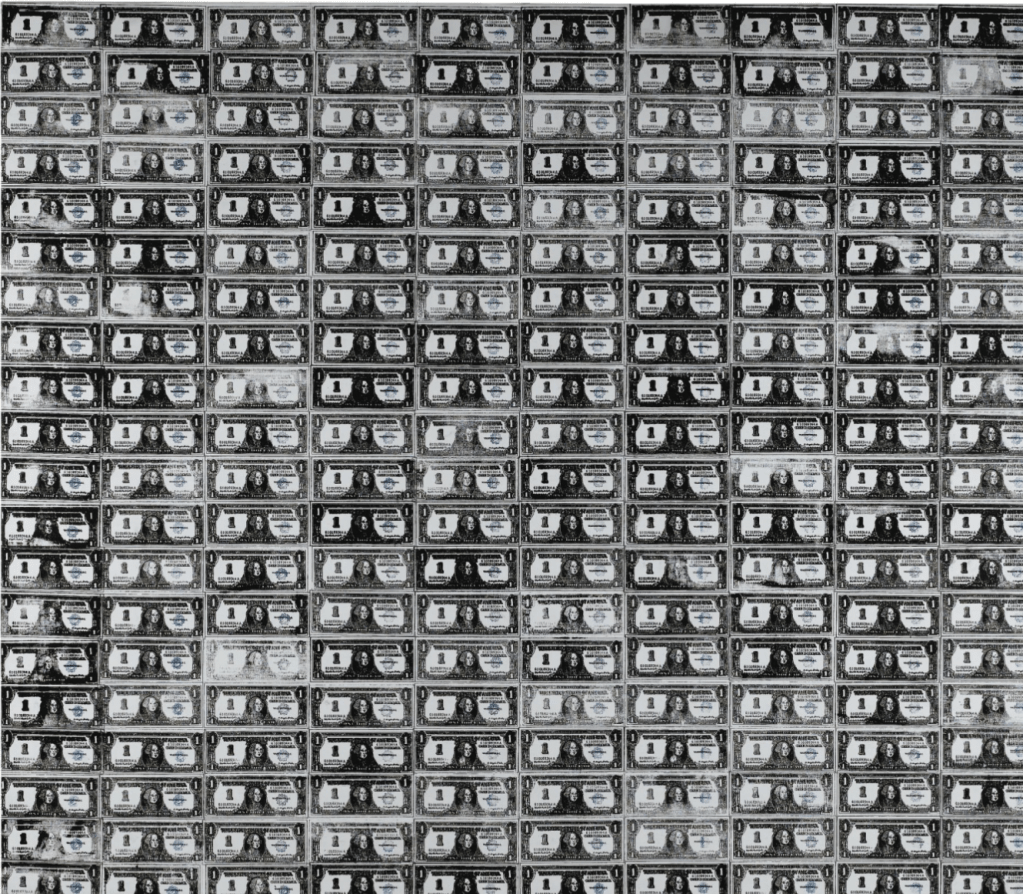

In 1962, Warhol produced a piece that asked just this. Using the silkscreen method for which he would become famous, Warhol painted two hundred dollar bills in a large grid. Maybe there was something of Jasper Johns here, a conceptual coup couched in Americana that would move him past the tyranny of Abstract Expressionism. That is until he added the preciously Warholian detail of pricing the painting at $200.[5] The parity between the price he demanded and the objects represented in the painting was understood as nothing less than an artistic attempt at coining money. The painting alone, as a dumb object on a wall, could have evoked American consumerism, financial capital, or any similar theme. And yet, by the insidious demand for a certain price for the painting, Warhol blew open the doors for a blast of conceptualism to agitate the cool of Pop. Unlike Duchamp, whose ready-mades such as his famous urinal forced the viewer to question the limits of what could count as art, Warhol made his viewers come to terms with the inexorable links between art and commerce.

Heidegger’s philosophy is, in fact, quite helpful in navigating the paradoxes that Warhol’s works pose for us. In “The Origin of the Work of Art,” Heidegger mentions in rather inspired terms that in the field of beings, in the field in which the recognition of the other is possible, the “clearing” appears as what encapsulates all beings and makes them intelligible. “That which is can only be, as a being, if it stands within what is lighted within the clearing.”[6] The paradox emerges when Heidegger mentions that a being can also be concealed “within the sphere of what is lighted.”[7] Thus the clearing, which bestows intelligibility to the beings one finds there, is also the condition for the possible concealment of others. Furthermore, “Each being we encounter and which encounters us keeps to this curious opposition of presence in that it always withholds itself at the same time in a concealedness.”[8] Why so? For Heidegger, for a being to conceal itself from us means that our knowledge of that being has encountered some resistance at the point “when we can say no more of beings than that they are.”[9] Concealment marks the beginning of our epistemological limits, just as it is also precisely the “beginning of the clearing of what is lighted.”[10] In other words, concealment begins when we can recognize that another being is even if we don’t know what they are. Concealment, Heidegger argues, is just this refusal of another being to lend themselves out to us in a pure transparency. Not only that, but concealment can also take the form of a being’s obscuring, hiding, dissembling, or denying another being, actions that occur within the clearing and not just at its limits, as in the case of pure epistemological refusal. “[T]he clearing,” Heidegger concludes, “is never a rigid stage with a permanently raised curtain on which the play of beings runs its course. Rather, the clearing happens as this double concealment.”[11]

This becomes important when Heidegger then defines truth as the “unconcealedness of beings,”[12] thus relating truth to the two forms of concealment: refusal and dissembling. In Heidegger’s most dialectical turn, he writes

The nature of truth, that is, of unconcealedness, is dominated throughout by a denial. Yet this denial is not a defect or a fault, as though truth were an unalloyed unconcealedness that has rid itself of everything concealed. If truth could accomplish this, it would no longer be itself. This denial, in the form of a double concealment, belongs to the nature of truth as unconcealedness. Truth, in its nature, is un-truth.[13]

The presence of truth is thus signified by the “concealing denial.”[14] Truth is, as it were, contaminated by concealment since, at least in this Heideggerean version, truth is not “an attribute of factual things in the sense of beings, nor one of propositions.”[15] Truth is a “happening,” a phenomenological situation where we perceive the reality of the other’s being even if at this moment our knowledge of the other is still limited.

Beings can and do present themselves as concealed within the clearing, thus revealing that other beings are concealed and dissembling. Taking this discourse in hand, can we not argue that the more Warhol concealed himself in his wigs and in his personas, the more, in the end, he revealed himself to us? What if we look at the facts of his upbringing? Would he have been as honest with his conservative mother concerning his sexuality, effeminacy, cold demeanor, and hard personality as he was with the cameras that captured all of this? Aren’t there things that he would have told an interviewer, however laconically, that he wouldn’t have told Julia Warhola? Can we not say that there’s a particularly Heideggerean dimension to the notion of the public interview, which, as it were, opens up a space in which the truth is demanded of a “being” in the form of a question even as the truth, as it is related, is concealed through the artifices someone as capable as Warhol could use to manipulate their public persona? The interview would thus be this open clearing where a being comes to us as being a being, but whose presence was simultaneously concealed, distant, not necessarily less truthful, but rather shadowed and dissembled. The same, I would argue, would apply to his art.

As with the clearing of being, there is something revelatory about the work of art. But insofar as the work belongs to the domain of truth, insofar as art remains “the creative preserving of truth in the work . . . the becoming and happening of truth,”[16] the work of art also has a relation to concealedness. In this dialectical relation, the work is thus not a pure revelation. Something of it, its thingliness or even its interpretable meaning, must remain half-opaque. Even if, as Heidegger says, this being of the work of art opens up the clearing of being, it does so on a terrain that necessarily allows for concealment. As Gopnik puts it:

[Warhol’s] true art form, first perfected in the days of Pop, was the state of uncertainty he imposed on both his art and his life: You could never say what was true or false, serious or mocking, critique or celebration. He himself billed this uncertainty as a major fact of existence: “You can never really know. People really lie. I mean, they can just lie about anything.”[17]

Warhol and Psychoanalysis

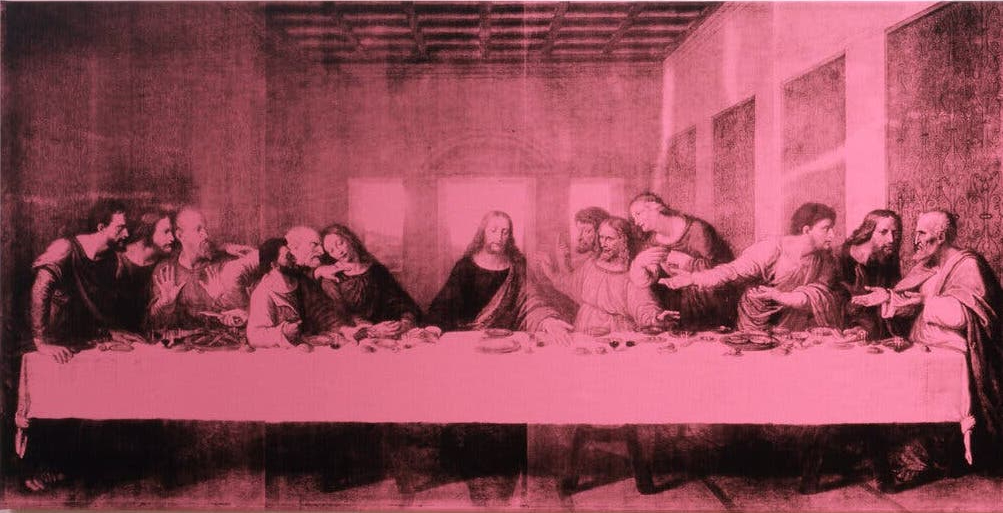

The technical facility with which Warhol could reproduce his paintings allowed Warhol to de-sacralize the Romantic supposition of the author as the tortured creator of original singular masterpieces. Not only could Warhol largely abandon the execution of his work to his assistants, but he could produce and sell many versions of the same work (though not all perfectly equal), allowing for great variations of design, details, and price points. “I think every painting should be the same size and the same color so they’re all interchangeable and nobody thinks they have a better painting or worse painting . . . even when the subject is different, people always paint the same painting.”[18] Gopnik adds that Warhol’s commitment to repetition provided a level of consistency that “tied together” his early pieces.[19] From a Lacanian perspective, it almost seems as if Warhol’s art played less on the imaginary plane than on the symbolic insofar as we understand the symbolic as the realm of signifiers and difference, and thus the realm where notions of iterability and repetition are most salient. We can see this in the pervasiveness of brands and prices in Warhol’s entire art production, from the earliest soup cans to the Last Supper series at the end of his life. As he would write,[20] “The moment you label something, you take a step—I mean, you can never go back again to seeing it unlabeled.”[21]

In 1963, an article in Time became the “first public account of Warhol as we’ve come to know him.”[22] It describes Warhol as a “pop artist,” listening to pop tunes, surrounded by “Movie magazines, Elvis Presley albums, copies of Teen Pinups and Teen Stars Albums.” More important is the assessment of Warhol’s cans: “the apparently senseless repetition does have the jangling effect of the syllabic babbling of an infant—not Dada, but dadadadadadadada.”[23]

The comment underscores how interesting Warhol’s work is to psychoanalytic thinking. Not only does the article recognize that Warhol’s Pop art was riding on Dada’s coattails, but it also sees its repetitive nature as an infantile characteristic—as regressive: Pop after Dada, as if the language of the history of art was itself mirroring the changing lexicon of a growing child.

In psychoanalysis, repetition is the emblematic behavior of drives and neuroses. A drive is characterized by its impelling force, its unforgiving compulsion or insistence towards some object (though the object, as Freud and Lacan never tire of telling us, is not as important as the drive function itself). Same with neurosis, which is characterized by the return of the repressed. What inhibits the everyday functioning of a neurotic is precisely a particular behavior that repeatedly and insistently gets in the way. Whether it was Dora’s aphonia or Hans’s phobias, a common thread is that they weren’t one-off events. They were repeated trends implying that something at the core of the unconscious was seeking disturbing satisfaction or entrance into consciousness. We could say, with Lacan, that repetitions are nothing other than the psychic evidence that there is an issue, that something problematic has been elicited.

Once we understand this, we can view this element of repetition in Warhol’s art as the emblematic site of a problem. When Warhol repeats Marilyn Monroe in the Marilyn Diptych or the Mona Lisa in the Thirty Monalisas or when he colors the Last Supper in multiple shades, we can argue that he is not showing these famous subjects as icons as much as symptoms, as if to reveal that the cult of the celebrity was symptomatic of a consumer culture awash in symbolic enjoyment even if it’s not too consciously aware of it. Warhol shows us that in the very act of repetition the sacrosanct place of the original is no longer secure and that all new iconic images will be iconic not because of the specialness of the one work of art that could capture them—the one canvas, the one sculpture—but because of the images’ pervasive appearance and reappearance within culture. It’s almost as if the image exceeds the work of art, and it is the canvas that has to chase after it. Like symptoms, the McDonald’s golden arches, the Coke bottle cursive, the bitten Macintosh Apple, and Mickey Mouse’s round ears appear and reappear on our way to work, in films, in films of films, in politics, and in our dreams, whether we want them to or not. Our culture’s addictions to marketing have turned these symbols into automatisms to the degree that they now seem like the necessary conditions we check for to determine whether any society is fully developed.[24]

Indeed, Warhol had an extraordinary capacity to recognize the symbols that encoded American culture. “What made him matter,” Gopnik writes, “was his ability to clue in to the obsessions that were shared across America, and then to come at them from the oblique angle of art.”[25] And precisely because his art was so expansive, so multifaceted and in tune with the symbology that America’s consumer class could easily recognize, Warhol was able to embed himself at the pinnacle of American high society, at once participating in its enjoyments while using it as artistic matter that he’d endlessly satirize.[26]

Queerness

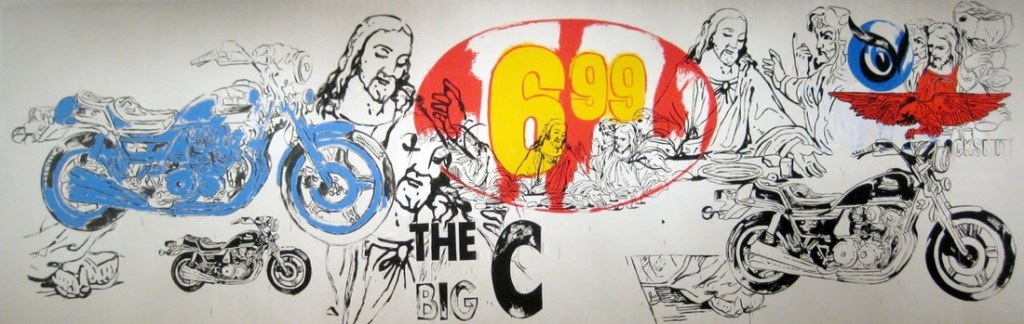

A Warholian work is never easy; it is never all-revealing. So, it is precisely the facile economic and commercial interpretations of his work that most feel like evasions of the work’s animus. They get stuck on what is the most superficial and most evident trait.[27] In short, interpretations of Warhol along purely economic lines read like positivistic analyses that evade, as always, what you could call the unconscious features in the work. We can only bring these features to light when we remember, at least, the contexts in which each Warholian painting emerges. For example, the “Big C” painting, which was exhibited as part of Warhol’s Last Supper series of 1986 and in the middle of the AIDS crisis, could well be read as echoing themes that would have been very resonant to someone witnessing the death of their loved ones due to AIDS. In one frankly awesome painting, Warhol included elements of homosexual leather culture (motorcycles), his Pop past (prices and brand icons), and marks of his religious commitments (Christ).

If Warhol’s art poses a question whose answer liquidates substantive meaning at the level of the subjects represented, then what remains, what survives his self-deconstruction is the titillation of desire. In other words, if we strip the soup cans or the Brillo boxes down to their most meaningless level—the level at which we see them only as pure posited objects—there will still remain the meta-aesthetic dimension of the artist’s choice, of Warhol’s having picked these objects and not others. The subjects taken as pure quotidian objects of consumption become meaningful in the choice, in the gesture of the artist who inscribes said choice within a panoply of other artistic choices all of which constitute, as a whole, a given aesthetic. Thus, if Heidegger was right and the work of art is the setting to work of truth, then the Warholian work, itself transgressive and transformative, illustrates the fact that an interesting transformation has occurred in the nature of truth after the Second World War.

As we now know by way of thinkers like Jean-François Lyotard, universal meaning did not survive 1945. The mores and structures that once depended on those universal meanings and values fractured and were consolidated into a multitude of relativisms. As a result, desires long suppressed (due to both repression and oppression), ranging from desires for colonial independence to desires for the other of the same sex, became the bases for new political programs and discourses. Truth, once held prisoner behind the bars of dogmatic universalist thinking, whether that meant Soviet socialism, European imperialism, or American capitalism, often at the expense of marginal discourses, now took the form of a multiplicity of desires, all of which claimed the backing of truth along experiential, molecular lines, so that, for example, the lived experience of a queer body and the lived experience of a Black body would both justify new political and existential aims that may have resembled and built upon each other, even though the truth claims these experiences justified might be rather different. Thus, what we see is the overtaking by desire of the field of truth itself, by which I mean not that the truth has ceased to exist nor that truth can be whatever anyone desires it to be, nor much less that identity politics have eroded the facticity upon which any stable democracy must rely;[28] but that the structure, the presence, the working of truth as such is no longer to be taken for granted and must be seen as filtered by each subject’s libidinal condition. If, in the regime of universalist thinking, truth was verbalized as the recognition of what is as it is, in today’s world, and certainly in Warhol’s art, truth is the verbalized recognition of what is as it relates to our desire.

This new transformation perhaps sees its best illustration in the Freudian notion of the refound object. Briefly put, the reality of the world is a conception that relates to our structural lack and is not a verity ascertainable on a purely positivistic understanding. Indeed, how can such understanding tell me that a rainbow “exists” when it is a phenomenon that precisely requires a human perceptual apparatus and is caused by a set of contingent environmental and spatiotemporal conditions to be registered? As Todd McGowan says, commenting on Freud’s essay “On Negation,” “things seem real to us insofar as they correspond to what we feel like we are structurally originally lacking.”[29] We can only ever engage in the process of reality-testing an object insofar as that object relates to our desire. As McGowan explains, when a person goes to a supermarket, what is “real” to the shopper is only what exists in relation to their lack, what stimulates their desire. The rest doesn’t “exist.” It loses its distinction. Other objects dissipate into a general sameness. In many ways, you could see Warhol’s soup cans as enacting the moment when the object has been refound if we consider that until Warhol chose the cans or the boxes as subjects of artistic rendition, they would have retained their anonymity in the supermarket.

Indeed, the Freudian concept of the refound object allows us to bring together two facts with respect to Warhol’s art: one, the cans (or whatever consumer objects) represent precisely desirable goods; and two, the portrayal of those objects is coldly realistic. The paintings are thus sites where desire and an objective real meet.[30] The Warholian work’s postmodernist deviations may take down substantive meaning and elevate the role of iterability, failure, camp, and mass production, but the strain of desire survives as a mark of irrevocable authenticity.

Whether we’re talking about his campy illustrations of the 1950s, the selection of icons of fame and celebrity of the 1960s, the nude “landscapes” of the 1970s or the Last Supper series of the 1980s—the running theme in all of these productions is a certain relationship to queer desire. It was an aesthetic derived from a man’s disjoint relation to the normative pleasures sanctioned by society, an aesthetic that precisely mirrors the cryptic silence and expectation, the anxious uncertainty, say, of a man cruising some park, laying his desire out, and yet, all the same, trying to remain hidden, trying not to reveal too much, hoping that someone will meet his gaze half-way to fish his pleasure out.

Gopnik even writes that it was Warhol’s experience with his queerness that facilitated his transition towards his “put-on” persona of the 1960s, that juvenile, cool-cat demeanor of his in which he’d answer the questions of exasperated interviewers by giving aloof remarks if not silence. As Gopnik writes, “There was no way to be homosexual in postwar America without self-consciously playing a role, because the culture didn’t leave you feeling that there was any ‘natural’ self you could inhabit.”[31] In other words, if you’re a gay man in the late 1950s, you live a double life. You learn how to put on a mask; you learn how to encrypt certain behaviors and the expression of certain desires. The subtle and playful queering of these boundaries is how you get camp. The gay man finds his niche in these interstices, realizing that life is just this act and that people get by just acting, even if most don’t know it.

You could even say that this mark of queer desire—the reason that queerness itself can become an aesthetic has to do with what lies implicit within it: Negativity. Regardless of the liberality of the society in which a queer desire emerges, that desire will always relate to itself as other insofar as that society continues to habitually and normatively apportion legal, social, political, and economic benefits to those whose desire falls within heterosexual normality while those whose desire exists outside that normality continue to struggle to justify and defend the authenticity of their unions and lifestyles. Queer desire will exist in an “othered” distance, a location perhaps illustrated by Warhol’s Silver Factory where the heterosexual, the quotidian, the normative, and the bourgeois were discomforted while the famous East Village superstars that thrived in it were magnetized into burning faster and, at tragic times, more dangerously.

This does not imply that just because queer desire avails itself of the “not,” of being “not straight,” non-normative, it loses anything of dignity or enjoyment. Quite the contrary. If what Freud said of the relationship between prohibition and enjoyment was correct, one can’t help thinking that the exact opposite is the case. Similarly, we should not think that despite its location in normative culture, “normal,” straight desire deserves special privilege or that it is even as straight as all that—not after Freud and Butler have shown us respectively that the sexual drive has a multifarious nature and that heterosexual positionality may depend on a prior melancholic foreclosure of homosexual object choice.[32]

Indeed, to be perfectly clear, the “negativity” of queer desire is a space or moment of thinking, mediation, and distance; it is opened up precisely at the point where we encounter Warhol’s paradoxes and repetitions, the camp, the obvious banalities and haunting traces; what he called, referring to his cans, the “synthesis of nothing.”[33] “Without those tensions and complications, and the distance they gave him from the mainstream, Warhol would never have become the great enigmatic artist he was,” writes Gopnik.[34] When you watch something like Warhol’s Sleep, an eight-hour film of a sleeping man, full of sensual but tame close-ups, we should not think that the animating desire that inspired that experiment was any different from the one that led Warhol to produce the Marylins with their far more subtle and implicit camp, their concern with glamor and kitsch. It is a sign of her artistic sensitivity that Jessica Beck, the curator of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, chooses to interpret the Shadow paintings of the 70s as being conversant with Warhol’s homoerotic “landscapes”:

“To think about Warhol as a gay man throughout a period where it would have been dangerous or taboo to talk about that side of his life in the work and then to put out work that is undeniably about queer desire is radical. When you sideline the Sex Parts, that’s part of that division and it’s happening in the art history, it’s happening in the archive. What can be talked about and what can’t be talked about? I think really it’s about seeing something like the Sex Part paintings on par with something like the Shadow paintings.”[35]

Warhol Today

Design and art were forever changed after Warhol. Not too long ago, I was walking with my mother, and we saw a man wearing a shirt with four of Walt Disney’s characters organized into four squares, their backgrounds all in different colors. Immediately, I recognized the influence of the Shot Marylins, and I wondered if the man had an inkling of an awareness that he was participating and even enjoying the symbology we inherited from Warhol’s innovations. As I mentioned at the beginning of this rumination, one either knows Warhol too much or too little. Once one traverses his biography one realizes that there remain censored aspects of his life. We then realize that we are in an interesting territory, one in which something of the subject is repressed at the same time that it doesn’t stop returning: in other words, we are in the realm of the symptom.

Our spectacular media environment adds to this insofar as it has made it possible for just about anyone to achieve unprecedented levels of fame (and infamy). This has produced a discourse that is reactivating the often-cited adage quoted by Warhol that “In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes,” thus rekindling Warhol’s relevance at a time in which entertainment found its profits in the superficial and attention-addled.

More interesting is the fact that it is perhaps because of this renewed interest in Warhol that you can see a growing tendency in people, ranging from those that orbited his circles to the critics and academics that take him as an object of study or derision, to wonder what Warhol would have thought about the problems of our times and, more tantalizingly, whether he could harvest from the chaotic morass of our current cultural landscape anything with which to break new frontiers in art. After all, this was what he did in the 60s when his Campbell’s Soup Cans marked the end of the reign of Abstract Expressionism, and in the 80s when his Interview magazine became the vehicle for what Warhol called “Business Art.”

So, if he were alive today, would he have liked TikTok and Twitter? Would he have seen this as a medium of art? Or could we say that unlike TV or radio, whose technological development coincided with modernism, social media, a postmodern phenomenon, cannot be expected to harbor any potentiality as an artistic medium? For something is quite curiously evident. Warhol’s technophilia was a product of his latent modernism: he was fascinated with the technological developments that could open new artistic fields, from the ballpoint pen to the Big Shot Polaroid. His films were lengthy, taxing, and challenging, much like a modernist novel or poem. And yet, his paintings were, as mentioned above, “obvious”; they were “examples of undiluted subject-ness.”[36] But they were also redolent with satire, irony, and, indeed, metalogical complexity—like a postmodern novel. In both situations, he maintained an unwavering commitment to realism, to simply letting be whatever subject or object he was interested in capturing on film or on the canvas. His Soup Cans are thus static, and the superstars in his films acted with minimal directorial input. They were told to be themselves, to let each scene unspool itself from the energy of their playful and random interactions. As mentioned above, the effect was a realism that the viewer could enjoy as a voyeur.

For this may have been, in the end, his greatest contribution: not that, as an artist, he showed us new ways of looking at the world. That is nothing more than a trite cliché by now. What he did was more important. He showed us new ways of enjoying. He made us into voyeurs of the sensational mundane, and in quite radical maneuvers such as in the Oxidations, he, perhaps more literally than figuratively, told us to take the piss out of art.

His life ended tragically during a tragic time. Still, he left behind an artistic legacy that we could describe, using John Richardson’s eulogy of Warhol in 1987, as “awesomely cool” and “awesomely prophetic.” He would’ve been pleased to know that his works fetch obscene amounts of money now, just as he would have been the first to point out that it is the art world’s original sin to think that the cost of a painting determines its worth. After all, so what? Why do we care that a Jackson Pollock is worth hundreds of millions of dollars if it is to end up locked away in one of the thirty yachts owned by a Saudi prince? Perhaps, that we continue to ask ourselves what Warhol would think of us belies our unwillingness to let Warhol go in the same frenzied way he never let go of the world while he was alive. For all his solitude, his taciturnity, and his vulnerability, he left us a symbolism of desire and love that hurts and transgresses and is never perfect but asks us always to spin and burn in silver like superstars.

[1] Blake Gopnik. Warhol. Ecco, 2020, 883.

[2] ibid. 884.

[3] Klaus Honnef hints that Pop art is a “kind of realism which was beginning to establish itself as an art form in its own right—without expressly claiming autonomy.” Klaus Honnef. Warhol. 1989. Köln. Translated by Carole Fahy and I. Burns, Taschen, 2021, 40.

[4] There is no shortage of art criticism, some of it coming from the likes of Bob Colacello, that tries to link Warhol’s Pop works to his Eastern Catholicism. With more nuance, Klaus Honnef argues that it is not the brands or figures—the subjects—represented in the paintings that are iconic but the paintings themselves. It is the artist’s “aesthetic act” that elevates a brand name into high art. On its own, it is insufficient. Cf. Honnef 52.

[5] “Art You Can Bank On,” Life, 19 September 1969, 56. Quoted in Gopnik 252.

[6] Martin Heidegger. Poetry, Language, Thought. New York, Harper, 1971, 51.

[7] Heidegger 52.

[8] ibid.

[9] ibid.

[10] ibid.

[11] ibid.

[12] ibid.

[13] ibid. 53.

[14] ibid.

[15] ibid. 52.

[16] ibid. 69.

[17] Gopnik 326.

[18] Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, 1975. London, Penguin, 2007, 149.

[19] Gopnik 846.

[20] It is known that Warhol relied on Pat Hackett and Bob Colacello as ghost writers. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol is a product of 3 minds: Colacello, who wrote an initial draft; Brigid Berlin, who commented on it; and Pat Hackett, who did the major construction. See Gopnik 777. According to Gopnik “‘I never wrote it, I never read it’ was the account Warhol gave to one of his old superstars” (780).

[21] Andy Warhol, POPism: The Warhol Sixties, Harcourt, 1980, 50.

[22] Gopnik 238.

[23] “Pop Art: Cult of the Commonplace,” Time Magazine, 3 May 1963, 74. Quoted in Gopnik 238.

[24] We should recall how significant it was that McDonald’s chose to leave the Russian Federation after it invaded Ukraine in 2022. The move was taken as evidence of McDonald’s’ loss of financial and political faith in the region. Images of the closed restaurant were quite a contrast to the glee with which Soviet Russians welcomed the first McDonald’s restaurant into Moscow in 1990, smack in the middle of Gorbachev’s reforms. Today, we could almost say that civilization means nothing less than the degree to which any community participates in the symbology of the shared global order. Apropos of this we should recall what Warhol wrote in 1975, almost as if to prefigure the coming of Lyotard: “The most beautiful thing in Tokyo is McDonald’s. The most beautiful thing in Stockholm is McDonald’s. The most beautiful thing in Florence is McDonald’s. Peking and Moscow don’t have anything beautiful yet” (Warhol, Philosophy, 71).

[25] Gopnik 27.

[26] Interpretations of Warhol that emphasize his obsessions with commercialism and celebrity culture are pervasive. You hear them incredibly often. They’ve appeared in places as important as Supreme Court opinions where they go as far as to frame the background of the justices’ legal debates. In the majority opinion in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, Justice Sotomayor opined that the Warhol Foundation’s use of a Warhol silkscreen of Prince, which had been based on Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of the same singer, did not constitute a transformative use of the original photograph and was thus not subject to “fair use” protection under copyright law. In contrast, she argued, “the Soup Cans series uses Campbell’s copyrighted work for an artistic commentary on consumerism, a purpose that is orthogonal to advertising soup . . . His Soup Cans series targets the logo. That is, the original copyrighted work is, at least in part, the object of Warhol’s commentary.” United States, Supreme Court. Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith. 598 U.S. ___ , 2023, p. 27. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-869_87ad.pdf.

Justice Kagan didn’t buy it. In her acerbic dissenting opinion, she wrote, “it may come as a surprise to see the majority describe the Prince silkscreen as a ‘modest alteration[]’ of Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph—the result of some ‘crop[ping]’ and ‘flat- ten[ing]’—with the same ‘essential nature.’ Or more generally, to observe the majority’s lack of appreciation for the way his works differ in both aesthetics and message from the original templates . . . For it is not just that the majority does not realize how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care.” (I have removed otherwise distracting legal citations.) Elena Kagan, Dissenting opinion. Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith. 598 U.S. ___ , 2023, p. 2. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-869_87ad.pdf.

[27] Blake Gopnik summarizes well the complicated nature of Warhol’s relation to commerciality, even when he was at his most commercial: “No matter how sold out his work could seem to some—it might look like he was shilling for canned soup or Hollywood or rich portrait sitters—there was always a little edge of distance, even of critique, that kept it feeling fresher than the competition” (162).

[28] It seems apropos to mention here that there is an unfortunate trend in certain psychoanalytic communities to denigrate the concept of identity tout court on the basis that identity, as per Lacanian theory, is an imaginary construct that covers over the fact that subjectivity is not “whole,” that it is split (by the unconscious, by the signifier, etc.). While I don’t disagree with the theory, I find that the vitriol surrounding the issue is unwarranted and politically unhelpful. After all, an identity may be fantasmatic, but this doesn’t mean that certain subjects don’t wager their destinies on those conceptions, as Trans folks demonstrate clearly. Indeed, shouldn’t the fact that there are subjects who are willing to risk it all on a certain sense of self create the occasion for us to step back and think longer, to mediate, to understand before we use analytic theory to dismiss it all? Regrettably for the Žižekians, this might be an issue where Butler shows a more tempered and, ironically, less hysteric approach.

[29] “Negation.” Why Theory. 5 February 2023, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/why-theory/id1299863834 41:04.

[30] You can even link Warhol to our understandings of the refound object by recalling the title of a 1963 gallery show at the Guggenheim Museum in which Warhol exhibited his artwork: “Six Painters and the Object” (my emphasis, Gopnik 295).

[31] Gopnik 477.

[32] cf. Judith Butler. The Psychic Life of Power. Stanford University Press, 1997.

[33] Quoted in Gopnik 229.

[34] Gopnik 53.

[35] “Shadows: Andy and Jed.” The Andy Warhol Diaries, season 1, episode 2. Netflix, www.netflix.com/title/810261421, 36:25. Blake Gopnik, in his biography of Warhol, identifies the progenitor image as being the shadows thrown by randomly arranged “cardboard” (824).

[36] Gopnik 230.

Leave a comment